kavedaa programming articles

Automatic UI generation with Scala 3's type class derivation

Scala 3 has a lot of cool new features. Among those is so-called type class derivation, which isn't really a single feature in itself, but rather a set of low-level technologies that enables the automatic implementation of type classes for certain composite types.

Basically if we have a type class (or trait) like trait Foo[A], we can use these technologies to write code that implements Foo for any A, if A is a product type (e.g. case class) or sum type (e.g. enum).

Can we (ab)use this for automatic user interface generation?

For instance, say we have:

case class Person(firstName: String, lastName: String, birthDate: LocalDate)

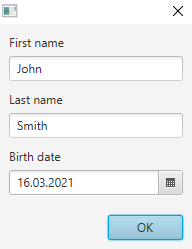

can we write code that enables us to use a simple one-liner like:

val dialog = new DerivedDialog[Person]

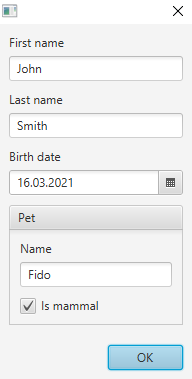

to automatically generate a dialog like this:

Yes, we can, and it this article we will see how.

Type class derivation basics

Let's first see how this type class derivation machinery works by implementing something simpler. Consider the following type class:

trait Transformer[T]:

def f(t: T): T

This has a single method that simply transforms a value into a another value of the same type. We use this just as an example, but it also has some similarity with the process of editing a value via a user interface, so it's not a bad place to start.

Now we can create given instances of this for some primitive types:

given Transformer[String] with

def f(x: String) = x.toUpperCase

given Transformer[LocalDate] with

def f(x: LocalDate) = x plusDays 1

If we also create a utility method like:

def transform[A : Transformer](a: A) = summon[Transformer[A]].f(a)

we can transform primitive values like this:

scala> transform("foo")

val res0: String = FOO

scala> transform(LocalDate.of(2021, 1, 1))

val res1: java.time.LocalDate = 2021-01-02

However, if we try to transform an instance of the Person class defined above, we get:

scala> transform(Person("John", "Smith", LocalDate.now))

1 |transform(Person("John", "Smith", LocalDate.now))

| ^

|no implicit argument of type transformer.Transformer[Person] was found for an implicit parameter of method transform

which is expected, since we have not implemented a Transformer for Person.

We could of course quite easily write a Transformer[Person]. But it's tedious, and programmes hate tedious work. So what if we instead could find a way to automatically create a Transformer not only for the Person class, but for any case class, given that we already have transformers for the individual elements of that class?

Here's how we can do that with the new Scala 3 features:

inline given [A <: Product] (using m: Mirror.ProductOf[A]): Transformer[A] =

new Transformer[A]:

type ElemTransformers = Tuple.Map[m.MirroredElemTypes, Transformer]

val elemTransformers = summonAll[ElemTransformers].toList.asInstanceOf[List[Transformer[Any]]]

def f(a: A): A =

val elems = a.productIterator.toList

val transformed = elems.zip(elemTransformers) map { (elem, transformer) => transformer.f(elem) }

val tuple = transformed.foldRight[Tuple](EmptyTuple)(_ *: _)

m.fromProduct(tuple)

There's a bit of stuff going on here. Notable new features being used are:

inlineMirror- some

Tuplefeatures

Let's look at it in a little more detail. Mirror.ProductOf is synthesized automatically by the compiler for all product types (e.g. case classes), so it will always be available here. This class contains meta-information about the case class that we can use for inspecting it.

First we summon given instances for Transformer for each of the element types of the case class:

type ElemTransformers = Tuple.Map[m.MirroredElemTypes, Transformer]

val elemTransformers = summonAll[ElemTransformers].toList.asInstanceOf[List[Transformer[Any]]]

For the Person class m.MirroredElemTypes will be (String, String, LocalDate). Using Tuple.Map we turn that into (Transformer[String], Transformer[String], Transformer[LocalDate]) which we in turn pass (as a type) to Scala's summonAll method. This returns a Tuple containing corresponding given instances for these types. We turn that tuple into a list (and remind the compiler of the type of that list).

Then we can implement the transformation method f. This takes an actual instance of the class we are operating on, such as a Person, and returns a new instance of that class, with the elements transformed by the individual transformers. First we put all the elements of the class into a list, and then we map each element with the corresponding transformer instance:

val elems = a.productIterator.toList

val transformed = elems.zip(elemTransformers) map { (elem, transformer) =>

transformer.f(elem)

}

Finally we put the resulting list back into a tuple, and use the fromProduct method on the Mirror to create an instance of the case class from the tuple:

val tuple = transformed.foldRight[Tuple](EmptyTuple)(_ *: _)

m.fromProduct(tuple)

And that's it! I have to admit to not completely understand how the inline stuff works, but the gist of it is that it allows the compiler to do the necessary type-level magic logic. So now we can do:

scala> transform(Person("John", "Smith", LocalDate.of(2000, 1, 1)))

val res1: Person = Person(JOHN,SMITH,2000-01-02)

The nice thing is that it already works recursively, which means that if we define our classes like:

case class Pet(name: String, isMammal: Boolean)

case class Person(firstName: String, lastName: String, birthDate: LocalDate, pet: Pet)

and make sure we have transformers for all primitive elements with:

given Transformer[Boolean] with

def f(x: Boolean) = !x

we can just do:

scala> transform(Person("John", "Smith", LocalDate.of(2021, 1, 1), Pet("Fido", true)))

val res0: Person = Person(JOHN,SMITH,2021-01-02,Pet(FIDO,false))

User interfaces in JavaFX

For the actual user interface generation we will use JavaFX, but the technique could probably be easily ported to other toolkits. Let's first take a quick look at how to create user interfaces in JavaFX manually.

JavaFX uses a "scene graph" which is a tree-like hierarchy of Nodes. Nodes can be "controls" like text fields and check boxes, or layout containers (or other elements not relevant here). For editing a Person like the one defined above, we could write the following code:

val firstNameField, lastNameField = new TextField

val birthDatePicker = new DatePicker

val content = new VBox(10) {

getChildren.addAll(

new VBox(5, new Label("First name"), firstNameField),

new VBox(5, new Label("Last name"), lastNameField),

new VBox(5, new Label("Birth date"), birthDatePicker)

)

}

and then put the content inside a Dialog (not shown here).

The Person + Pet example would be slightly more complex. Instead of writing it, let's just move on and automate it instead.

Generating the UI

For editing the contents of a case class we need to generate an input control for each element in the class, corresponding to the type of the element. So that for String we need a TextField and for Boolean we need a checkbox, and so on. We also need to be able to set and retrieve the value of the control, as well as render it on the scene graph.

We start by putting these requirements into a simple type class:

trait Editor[T]:

def getValue: T

def setValue(x: T): Unit

def container(label: String): Container

The Container is just an intermediate step for abstracting away rendering of the nodes onto the scene graph. We define it like this:

enum Container(label: String):

case Primitive(label: String, node: Node) extends Container(label)

case Composite(label: String, containers: Seq[Container]) extends Container(label)

Then we implement instances of Editor for some primitive types:

given Editor[String] with

val textField = new TextField

def getValue = textField.getText

def setValue(x: String) = textField.setText(x)

def container(label: String) = Container.Primitive(label, textField)

given Editor[LocalDate] with

val datePicker = new DatePicker

def getValue = datePicker.getValue

def setValue(x: LocalDate) = datePicker.setValue(x)

def container(label: String) = Container.Primitive(label, datePicker)

Now we can write the derivation of Editor for any case class:

inline given [A <: Product] (using m: Mirror.ProductOf[A]): Editor[A] =

new Editor[A]:

val labels = constValueTuple[m.MirroredElemLabels].toList.asInstanceOf[List[String]]

type ElemEditors = Tuple.Map[m.MirroredElemTypes, Editor]

val elemEditors = summonAll[ElemEditors].toList.asInstanceOf[List[Editor[Any]]]

val containers = labels.zip(elemEditors) map { (label, editor) => editor.container(label) }

def getValue =

val values = elemEditors.map(_.getValue)

val tuple = values.foldRight[Tuple](EmptyTuple)(_ *: _)

m.fromProduct(tuple)

def setValue(a: A) =

val elems = a.productIterator.toList

elems.zip(elemEditors) foreach { (elem, editor) => editor.setValue(elem) }

def container(label: String) = Container.Composite(label, containers)

This is very similar to the derivation of Transformer. The one additional feature used is that here we also get the element labels using constValueTuple[m.MirroredElemLabels] so that we can render these on the UI.

Finally, we need a way to render the UI elements to the scene graph. We want this to customizable, so we create a trait Layouter that takes a Container and returns a JavaFX Node:

trait Layouter:

def layoutPrimitive(primitive: Container.Primitive): Node

def layoutComposite(composite: Container.Composite): Node

def layout(container: Container): Node = container match

case primitive: Container.Primitive => layoutPrimitive(primitive)

case composite: Container.Composite => layoutComposite(composite)

We also provide a default implementation for it:

object DefaultLayouter extends Layouter:

def layoutPrimitive(primitive: Container.Primitive) =

VBox(5, new Label(primitive.label), primitive.node)

def layoutComposite(composite: Container.Composite) =

VBox(10, composite.containers.map(layout)*)

There is one crucial thing missing. The documentation for given instances says that:

"A given instance without type or context parameters is initialized on-demand, the first time it is accessed. If a given has type or context parameters, a fresh instance is created for each reference."

This means that if we have several String elements in our case class, only one given Editor[String] will be created. This is clearly not what we want, since there then also will be only one TextField shared by those elements. Instead, we want to create a fresh instance of Editor[String] for each reference.

We can achieve that by using a dummy context parameter. With some clever naming, it also reads quite well:

trait FreshInstance

object FreshInstance:

given FreshInstance = new FreshInstance {}

given (using FreshInstance): Editor[String] with ...

We conclude by setting up a Dialog like this:

class DerivedDialog[A >: Null : Editor](value0: Option[A] = None) extends Dialog[A]:

val editor = summon[Editor[A]]

val layouter = DefaultLayouter

val content = layouter.layout(editor.container(""))

getDialogPane.setContent(content)

getDialogPane.getButtonTypes.add(ButtonType.OK)

setResultConverter { (dialogButtonType: ButtonType) =>

if (dialogButtonType == ButtonType.OK) editor.getValue

else null

}

value0 foreach editor.setValue

end DerivedDialog

and with an additional primitive Editor[Boolean], some tweaking of "camel cased" label strings, and some enhancements to the container/layouter logic (all which are left as exercises for the reader, or you can see the complete code), we can simply call:

new DerivedDialog(Some(Person("John", "Smith", LocalDate.now, Pet("Fido", true))))

to generate this dialog: